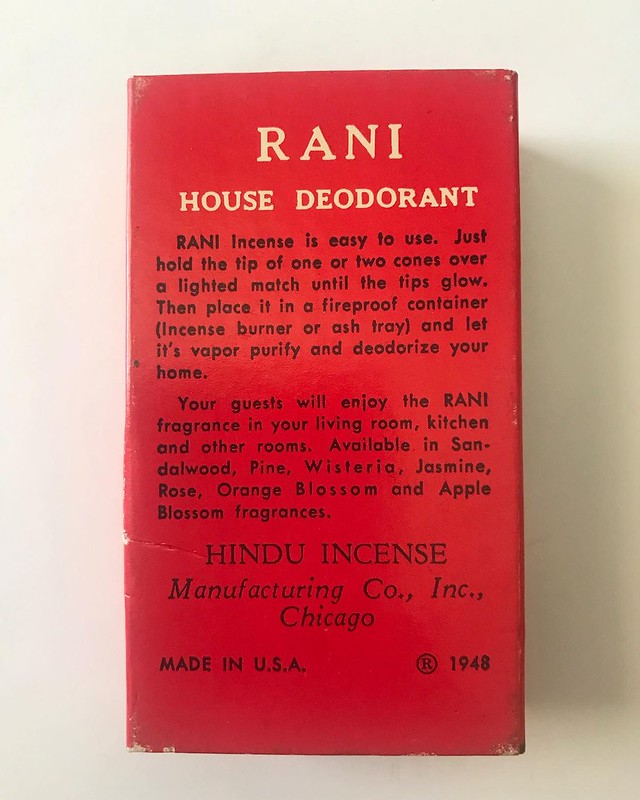

Both my parents were born during the 19-teens and weren’t what you’d call “hippies.” We had something associated with hippies, though — incense. RANI incense cones, to be precise, usually pine. Gift? Sale? I don’t know, but my mother liked them even if we used them sparingly. I’ve continued the tradition, buying incense (if not RANI) sporadically over the years.

Something made me think of RANI, so I looked up images of the box and found RANI, marketed as “house deodorant,” came from Chicago 60616. According to the trademark database the Hindu Incense Manufacturing Co. , Inc., was located at 2620 South Dearborn St. Office? Factory? I may never know. Sadly, today it’s a vacant lot. You can sometimes find the remaining boxes for sale on sites like eBay and Etsy.

More about the RANI mark:

Word Mark RANI

Goods and Services (EXPIRED) IC 003. US 006. G & S: INCENSE. FIRST USE: 19270415. FIRST USE IN COMMERCE: 19270810

Mark Drawing Code (5) WORDS, LETTERS, AND/OR NUMBERS IN STYLIZED FORM

Serial Number 71527404

Filing Date July 5, 1947

Current Basis 1A

Original Filing Basis 1A

Registration Number 0500209

Registration Date May 11, 1948

Owner (REGISTRANT) HINDU INCENSE MANUFACTURING CO. CORPORATION ILLINOIS 2620 SOUTH DEARBORN ST. CHICAGO ILLINOIS

(LAST LISTED OWNER) GENIECO, INC. CORPORATION BY CHANGE OF NAME FROM ILLINOIS 200 NORTH LAFLIN ST. CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60607Assignment Recorded ASSIGNMENT RECORDED

Type of Mark TRADEMARK

Register PRINCIPAL

Affidavit Text SECT 15.

Renewal 2ND RENEWAL 19880511

Live/Dead Indicator DEAD

Genieco lead me to the current Gonesh brand website, from which I learned:

In 1923, a Lithuanian immigrant named Radzukinas acquired a small company, The Hindu Incense Company. For business purposes, he changed his name to Radkins and changed the fortune of his small company by dedicating himself to the manufacture of quality charcoal incense cones and incense burners. Laurent Radkins operated the Hindu Incense Company successfully from the 1920s to the 1960s.

In the mid-sixties, the second generation of the Radkins family entered the business and Genieco, Inc. was born. Soon, the product offering was expanded to include incense sticks. The new brand name was GONESH®, named after the Hindu Elephant Boy, the God of Luck. The name Gonesh was trademarked in 1965.

The Chicago-based Hindu Incense Manufacturing Co., Inc., owned and run by a Lithuanian immigrant, marketing made-in-U.S.A. “house deodorant” incense cones to Greatest Generation housewives — a very American American dream.