(Beware gruesome fibroid image downstream.)

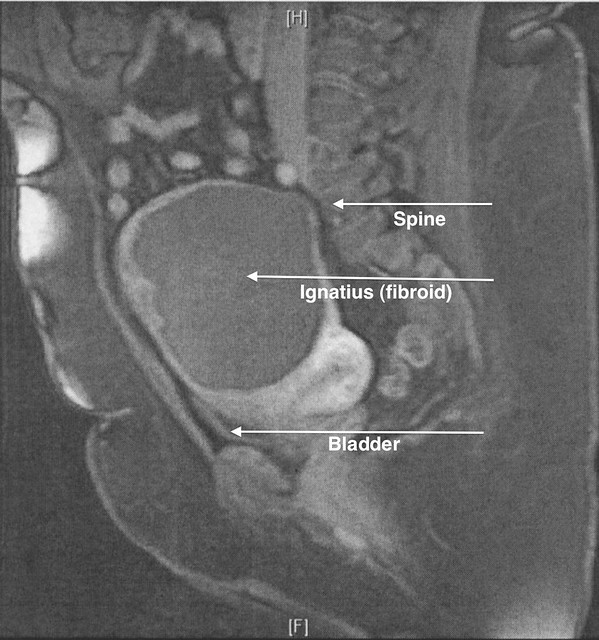

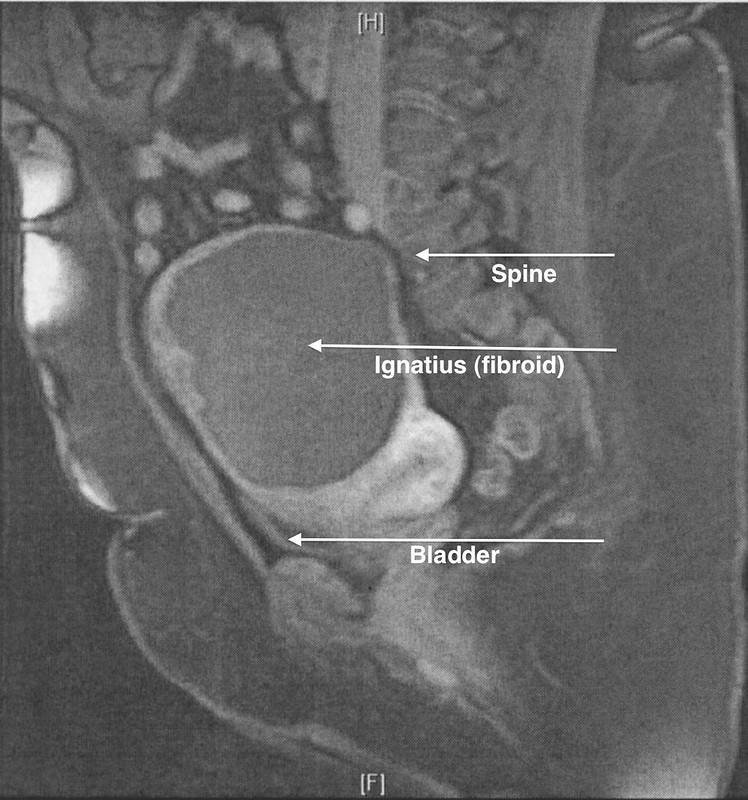

After an August 2008 uterine fibroid embolization, or UFE, failed to relieve me of Ignatius the tenacious fibroid’s symptoms — bulkiness, frequent urination, and possibly the lower back and leg pain that sometimes made walking even easy distances painful and tiring — I scheduled a laparoscopic myomectomy for July 27, 2009. In this outpatient procedure, a laparoscope is inserted through the navel, and the fibroid is sliced, diced, and extracted through several small incisions compared to a single large one. The surgery takes longer, but the recovery period is shorter.

Beforehand, I felt the same way I’d felt about the UFE — I was going to start the day relatively healthy and was choosing to end it, and to spend many days after it, in pain and discomfort. I didn’t hesitate, but it struck me a year ago and again now what an odd choice it seemed, especially because I had become so accustomed to the symptoms that they seemed normal and endurable. I knew, though, that I never felt very good anymore. Sometimes I wondered, too, if the growing sharpness of temper that I’d been experiencing weren’t attributable in part to the fibroid’s effect.

In short — no pain, no gain.

For a laparoscopic myomectomy, you must undergo something I’d never done — a bowel cleanse. On the remarkably cool and pleasant Sunday before the surgery, I spent my time swallowing a noxious liquid while hovering within 10 to 15 feet of the toilet. By 9 o’clock, I was sure that the pain I was in then was sure to be the worst of the whole affair.

Of course, it was just the beginning.

On Monday morning, I threw enough into a tote bag to keep me entertained in the waiting room — pen and pencil cases, journal, paper, The Bride of Lammermoor — plus the usual travel practicalities, like tissues and an umbrella. I also took my new iPhone GS, but not the adapter — I wouldn’t need that during surgery or the brief period of in-hospital recovery.

It’s too bad my brain didn’t regurgitate the slogan from the old commercial at just that moment: “Don’t leave home without it.”

I arrived almost exactly on time, at 8 a.m., and sat in the waiting room only a few minutes before I was called; there was very little time in which to become anxious, let alone break out The Bride of Lammermoor. I was escorted to a bed, where an experienced nurse introduced herself and began her ministrations, including the dreaded catheter.

I had been afraid of that.

Dr. M.’s resident came in and introduced herself. The anesthesiologist and his resident came in separately and introduced themselves. Even further down the food chain, a medical student introduced himself. I was the center of a lot of attention, which I’m not used to.

The anesthesiologist, who seemed distracted, noted my high TSH and low level of Vitamin D, although he confessed he didn’t keep up with the recommended ranges. “Really?” said the nurse. “It’s all the rage now — thought to be behind a lot of health issues.” “Like diabetes,” I contributed. “Like diabetes,” she agreed. The anesthesiologist appeared to be deferential on this point. “I follow it because it’s in the news so much,” the nurse explained.

The anesthesiologist left his resident behind to do the IV honors. She offered them to the nurse, who said it was up to the resident. “This isn’t the first time I’ve done this,” the resident said brightly. “And it’s not the second time, either.” If it was the the third time, it was not the charm, for after carefully and laboriously tapping a vein, she couldn’t get blood to come back even as the nurse was telling me, “I can do it because I’m old.” Later, the anesthesiologist tried a different vein, which he pumped up and which mysteriously disappeared as he tried to draw blood back. “It was there, but now it’s gone.”

I’m used to having deep, small, uncooperative veins, so none of this surprised me. I don’t recall who finally drew first blood or when.

My surgery was to begin at 9:30 a.m., but there was a slight delay. I went through the double doors at around 9:45 a.m., then promptly conked out, no counting needed. I’m not even sure how.

When I came to, I had the very odd but very clear sensation that it was late in the day. I did the mental math — two to three hours for surgery, say another two hours for recovery — and couldn’t reconcile my memory and calculations with my sense that the afternoon was far advanced. I turned to look at the wall clock, which, if I squinted, I thought I could read without glasses. Big hand on the 5, little hand on the 6. 5:30 p.m.

That couldn’t be right.

I looked again. Same result.

Uh-oh.

As people bustled about me and asked me how I was doing, I wondered if the extended time frame meant missing body parts.

Then I lay in Room 1462, overlooking Lake Michigan, I wasn’t in much pain, and if it hit me I had a button to push every 15 minutes as needed. I had time if not clarity of thought to wonder what kind of interesting circumstances or complications may have arisen.

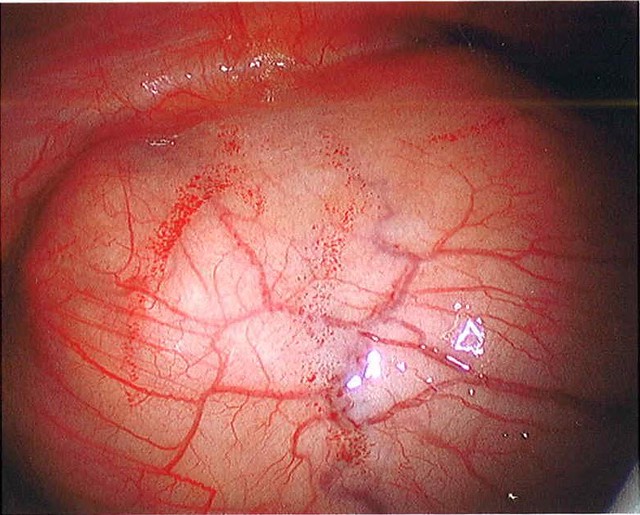

Later that evening, Dr. M. came in to tell me the story. I don’t fully understand it, so I wouldn’t want to be quoted on chronology or cause and effect. The short version is that issues with CO2 absorption, combined with the fibroid’s calcification, led to the decision to switch from an outpatient laparoscopic myomectomy to a mini-laparotomy to ensure the entire fibroid was removed. Ignatius, which was described using the precise medical term “ginormous” and which was demonstrated with a show of surgical hands, proved to be “hard as a rock,” having calcified after the UFE.

“So that’s the good part,” he said encouragingly.

“Yes,” I said, having a distinct feeling there was more.

There was.

For the first time in his experience, or any experience he knew of (including, as he later mentioned, that of his father, who had been a gynecologist for 40 years), an instrument (a tenaculum) had broken, and a small piece, one-fifth of inch in size, was now embedded somewhere in my tissues.

Ah. My very own piece of shrapnel.

While I was coming to, or shortly after, I think, x rays had been taken to track down the tenaculum tip. Dr. M. explained that the problem with x rays is that they don’t show where such an object is in three dimensions. In my anesthetized stupor, I suggested an MRI because I knew it would produce a 3D image. Dr. M. seemed to think this a brilliant idea, although later I marveled that I would even mention undergoing an MRI, which I, like most, don’t enjoy. He consulted with Dr. V., the interventional radiologist, who being more expert than I about medical imaging, in turn suggested a more efficient CT scan.

In the meantime, J. came in bearing gifts — flowers, candle, hand soap, “Get Well” balloon, and his Flat Eric to keep me company. After all that anesthesia, I could not keep my eyes open for more than a few moments, so I’m sure I was dull company. When I slept, it was as though dead. The frequent interruptions by the staff — to take my vital signs, to change IV bags, to look at my abdomen, to ask me about bowel movements, etc. — barely broke my sleep.

I found that early mornings began with a visit from Dr. M.’s resident with subsequent visits by other residents — never the same one or two twice — and the medical student I’d met Monday morning. While the residents asked questions, checked my abdomen, and performed other medical ablutions, the medical student seemed limited to asking questions and learning bedside manners. Before leaving, he would reach for and squeeze my ankle through the covers in a way that, in an experienced physician, would be reassuring but in this case was mostly awkward. As each morning’s residents came in, often waking me up from a sound sleep, I did appreciate being part of their educational experience in some infinitesimal way, and wondered if they’d seen my surgery or how much they knew of my case.

It was Tuesday, I think, that Patient Escort Services came to take me for a CT scan. From one day to the next, I had become as weak as an infant. I was sore, but it’s not that it hurt me to sit up or to transfer from the bed to the gurney. It simply took all my strength just to move from a prone to an upright position. Each time, I had to reach for one or more helping hands.

My room was in Prentice Women’s Hospital, while the CT scan equipment is in Galter or Feinberg Pavilion. We descended into the bowels, then proceeded what seemed an interminable distance. I don’t remember much except the surreal sensation that comes naturally with being wheeled on a gurney through long stretches of hospital basement hallways, broken mainly by scenic paintings, automatic external defibrillators (adult and child versions), and emergency signs and equipment. I also recall the weakness I felt transferring onto the CT bed and back, the hands reaching to help me, and how quickly it was done — in that sense, much preferable to an MRI.

I don’t remember much of Tuesday or Wednesday, which were largely featureless. I used my iPhone as long as the battery lasted. I figured out how to use the room’s TV/computer system, which seemed to hark back to the old WebTV. I watched students play baseball on the two diamonds below and the boats in the harbor and on the lake. I began to feel that I had never really learned how to live and that I had missed out on much in life, that the ball players, dog walkers, and boaters were all privy to secrets and pleasures that elude me. And I chafed at my constant restraints, the catheter and the IV. Finally, I don’t know when, the catheter was removed, bloodily and painfully, which gave me the freedom if not the energy to roam the halls, including the one circumference prescribed. I discovered a patient/family education center and a visitors lounge, both with computers, which I used to email Virgil and others.

By Tuesday dinner, I was deemed capable of a solid diet, and I was starting to feel hungry, so I ordered perhaps a little too ambitiously. I learned later that, if I had not ordered something, dining services would have called me. If your doctor has ordered a diet, they don’t let you get away with not eating, whether you wish to or not.

I felt okay yet not good on Wednesday. I thought that if I could just go home, I could rest and feel better, as I had after the UFE. It didn’t help that was I was fighting constant nausea and even had an incident in the handy bedside basin. I was told that one of the primary conditions of my release was the ability to keep oral pain medications down — something that nausea and vomiting were making problematic.

By Thursday afternoon, though, I wanted out. Although I sensed some reluctance, I was finally deemed ready for prime time, and J. agreed to pick me up after work. He arrived at 7 p.m., and we set off, first for Walgreens, armed with prescriptions.

At the pharmacy, it took longer than I expected, and after 15 minutes or so I started to wonder if a trip outside to get the basin I’d thoughtfully brought with me was in order. The nausea I thought was under control hit me hard. Although vomiting provided no relief, it probably did raise the eyebrows of the fellow who saw me emptying the basin, I thought discreetly, into the bushes outside the store.

Once home, I set J. up as best I could, showered, and fell into bed — where I could get only snatches of sleep between the terrible gas pains in my bowels and the equally awful nausea/acid and trips to relieve it, followed by the need to clean up the mess. It was the most vile vomiting I’d ever experienced, almost as though my internal organs had liquidated and were being voided through the mouth. It reminded me of the beef bouillon I’d had Sunday, as though it had fermented in my stomach for the past 72 hours.

I’m not sure when I’ve ever felt more wretched. And I had only myself to blame for pretending my symptoms were better than they were.

By 4 a.m., I was shivering uncontrollably. Later, after I had closed the window against the refreshingly cool night air, I started to sweat. My esophagus was in acidic flames, and even I had had enough. I called Dr. M. at around 5:30 a.m. To my surprise, he answered. He asked me my temperature (I didn’t know then, but took it a few minutes later — 102.4ºF), asked other questions, and told me to come straight back to the 14th floor of Prentice. All I wanted was that fire in my esophagus put out and to stop feeling so woozy. I roused J. and packed my bag, this time, remembering to include the iPhone adapter as well as my sponge bag — even in my feverish state I had that much presence of mind.

By 6 o’clock we were on Lake Shore Drive, me with my window rolled all the way down so the 60-degree wind could take the edge off the fever and sweating.

At the hospital, there was some delay with security, and I dragged myself to a seat while they figured out what to do with me and J. dealt with the valets. On 14, I veered instinctively toward Room 1462, which had since been occupied, but J. and my hospital escort firmly steered me toward Room 1464. After I was settled on the bed and my bag stowed, J. went to work, and I was left for quite a while to contemplate the unrelenting burning in my esophagus. Over the next couple of hours it dissipated, the nurses finally started an IV with antibiotics (being more concerned about the fever), and I accustomed myself to the thought of another night in the hospital.

Dr. M. wanted to make sure the sliver hadn’t moved, and so I was scheduled for another CT scan at 3:30 p.m., this time with and without contrast dye. Through some snafu or other, I wasn’t picked up until shortly before 6 p.m. I was still on pain medications, so I wasn’t in much pain, but I was in no condition to do anything except send emails through the WebTV-like room system, watch the weather, try to find something on television that wasn’t unbearable, and otherwise kill time until 3:30 p.m. and then past it.

Not long after Dr. M. had dropped in Friday afternoon, I had developed diarrhea — a sign that my bowels had come back online, if imperfectly. “That’s good!” he said enthusiastically when I told him later. “Do you always have that effect on people?” I shot back, which made him shake his head ruefully. Even Monday night J. had commented that my “wit” never left me, even under the influence.

By the time Patient Escort Services came for me before 6 p.m., I wasn’t sure I wouldn’t embarrass myself — at one point, either during my first or second visit, I’d already had a soiling incident. Sure enough, while waiting I had to go. And go again. And again. Just as they were about to run me through the machine the first time, without dye, I said, “I have to run,” and I did. In all, I made six or eight trips to the CT scan area’s facilities. At least at a hospital, most are sympathetic.

Next came Phase II — consumption of two 450ml bottles of barium sulfate, the contrast dye solution. Whimsically, one was labeled, “Berries,” the other “Apple.” (My first choice, “Banana,” which I thought least likely to aggravate my ongoing nausea, was unavailable.) Because of the nausea, I had warned everyone that I that I might not be able to keep the stuff down. The taste and texture didn’t help.

I was distracted by a conversation with a fellow patient, who sported a kerchief over her head and a deep red sickle wound under each eye. She looked like she’d been in an accident or on the losing end of domestic violence. She told me that the chronic sinus infection that had plagued her had proved to be a sinus tumor and that it had been removed the old-fashioned way — by going down through her head. “I look like I’ve been in a wreck, I know,” she said. Then, using J.’s words almost exactly, she added, “You, on the other hand, look fabulous. May I ask why you’re here?” “That’s because you can’t see my belly,” I answered. Not only did it look like a Frankenstein experiment, with the incision through the navel, two large and two small laparoscopic “ports,” and the larger mini-laparotomy incision on top of my appendectomy scar, but it was grotesquely distended with gas and distorted, with the bottom of the old scar even more pulled in and a bigger divot missing — not a sight for the squeamish or delicate.

I drank the two bottles within the allotted hour (it was now 8 p.m.) and hinted that I couldn’t be held responsible for keeping it down if there were any delay. Coincidentally, I was next — and somehow I did manage to keep it down. In fact, I think that by this point I had nothing left to give at either end, although the queasiness continued.

In the back of my mind, I wondered if J. had stopped by during the height of visiting hours and found me missing. When I was wheeled back into my room at 8:50 p.m., there he was, handing me a note about how he had to go back to work and how he had scrounged dinner at Argo Tea, discovered the hospital’s wireless network for guests, and fallen asleep over his iPod Touch. He stayed with me for a while, lured by the possibilities of wireless downloads. He really had to go, however, when around 9:20 p.m. I started to drool involuntarily and ran for the bathroom, saying, “Oh, I’m going to throw up” (although, as it turned out, the nausea passed and I didn’t).

“Uh-oh, well, I really do have to get back to work,” he replied. With that, my “nurse” unceremoniously bailed with unusual alacrity.

The CT scans revealed that the tenaculum tip was still in the abdominal muscle. They also revealed another unwelcome guest — a “big” gallstone, which was possibly the culprit behind some pancreatic inflammation, the nausea, and even fever.

I was scheduled for an ultrasound the next day to get a better look at my gallstone and the inflammation. This time, unlike for the previous night’s CT scan, I was taken lying down on a gurney against my will. The reason for this became clear, though, as the ultrasound technician performed his examination of me on the gurney — no transferring needed. It wasn’t too bad, except on a few passes he dug the wand into my tender abdomen. Owww. I asked for his unofficial verdict. “Your gallstone looks like it’s between one and one and one-half inches,” he answered. “That doesn’t seem that big,” I said later to Dr. M., who looked surprised and said, “It is. Typically gallstones are described in terms of grains of sand.” Oh.

The ultrasound also showed the inflammation was under control, probably thanks to the antibiotics. My temperature was consistently normal, the tenaculum tip was ruled out as a cause, and I was deemed fit to try to eat again. Indeed, I was told this time that if I could keep Saturday dinner and Sunday lunch and breakfast down, as well as oral medications, I could go home Sunday.

On Saturday afternoon I noticed the boats in the harbor pulling up quite closely to each other in rows. The nurse who came to reinstall my recalcitrant IV told me that the boaters pass from vessel to vessel drinking and having a good time, while the police keep a cautious eye on the festivities. It sounded like they do this a few times a summer as a tradition.

In the meantime, one of us noticed that I had developed ugly red welts on the insides of both forearms — an allergic reaction that mystified everyone as I’d been on the antibiotics for a while, and they thought the contrast dye an unlikely culprit for this delayed response. (I read later that it may have been additives.) Congratulations to me — I’d just earned several doses of IV Benadryl.

When Dr. M. came in after 9 p.m., sporting a sweat suit, he apologized for his tardiness and explained he’d had a commitment to his daughter. I was impressed he came in at all. By this time, my arms had cleared up, but when he took the obligatory look at my abdomen, he spotted welts all over my upper thighs. My body had not liked something.

Later, he was working at a computer in the Patient Care Center when I took a spin around the floor in the hope that exercise would act as a sleep aid. When he saw me pass by on the return trip, he seemed startled. “You walk faster than I do,” he observed. I don’t know if this is true, but by Saturday night I did feel much better than I had 40 hours earlier, and there was more of a spring in my step, I’m sure. Now if only I could keep down two more meals.

Dr. M. had found my dinner choice of whole wheat toast and cooked carrots “interesting,” while the nurses weren’t happy when they learned, too late, of it. “No whole grains, no vegetables, not with diarrhea,” they said. “In this case, fruits and vegetables aren’t healthy.” One recommended eggs or macaroni and cheese. Later, the new shift nurse dismissed eggs as “too fatty.” So for breakfast I ate white toast and drank four ounces of apple juice over a three-hour period, just enough to claim I had eaten. By lunch time, I wasn’t hungry. and I tried to sleep through it. This is when I found out that there is no evading dining services. If you are supposed to be eating, they will call you, wake you out of a sound sleep, and patiently wait for you to make up your mind. I asked her for recommendations, and she suggested eggs as “an easily digested protein.” I mentioned the nurse’s concern about fat, and — why had I not thought of the obvious? — she pointed out that they can be scrambled, etc., without the yolk. Eggs it was, plus one of the three apple juices they had left for me in the morning.

The IV was removed at some point on Sunday, and by noon I had, according to my purse pedometer, walked 1.01 miles, another feat that impressed Dr. M. That was my final burst of energy for the day because, after all that activity, the equivalent of two eggs, and the third and final apple juice, I didn’t feel like stirring.

Around 2 p.m., while those outside my window were savoring another perfect Sunday, I conked out hard. I’ll never know how long I might have slept because almost exactly at 4 p.m., a knock at the door interrupted a particularly intriguing dream. It took some time and effort to rouse myself, by which time a woman had bustled in, saying perkily, “Respiratory Services with oxygen!” Clearly, this wasn’t intended for me, although earlier in the week I had been chided by a nurse or two for not using my deep breathing visualization toy when in bed. “When I’m in bed, I’m usually asleep and can’t!” I’d retorted. They’d looked at me strangely.

Dr. M. made an appearance, this time in a t-shirt and shorts over which he’d thrown a lab coat to look more official. Maybe I said something, because he mentioned that when he comes downtown for only one thing he drives his vintage convertible. I told him he hadn’t had to come just to see me, but perhaps he did, because I was soon to be released. Free at last! For some reason, though, I had become very depressed during the day, which I mentioned and which I think he’d noticed. It may have been the prospect of going home alone, of not knowing what I was going to do with myself, and of uncertainty all around, but I also thought it might have been attributable to the effects of anesthesia, change, and strangeness, combined with my unhappy memory of Thursday night and Friday morning.

The nurse called in a couple of prescriptions to Walgreens (which is what I should have had done on Thursday) while I packed and waited 30 to 45 minutes for Patient Escort Services. Although capable of walking, I’d opted for a wheelchair because I still felt weak and lethargic, or just tired.

It turns out that cabs don’t come by that way often, and both my escort and one of the valets ventured out in search of cabs for me and for a family that was also waiting with a discharged patient. Finally, a cab pulled up to drop a woman off, and I anxiously asked him if he accepted credit or debit cards. My escort stepped up with a remonstrance about letting the previous passenger settle the fare with the driver, but I wanted to know the answer because if he didn’t, I’d cede my place to the waiting family. There’s nothing like being lectured about manners at such a time!

It worked out. The driver waited for me at Walgreens while I picked up and paid for the prescriptions and got cash back (why hadn’t I thought of that before, which would have spared me the lecture?).

And so ends the saga of Ignatius, the tenacious but benign fibroid (according to the pathologist). According to Dr. M., its post-embolization size was 12 centimeters, and it weighed 1,074 grams. I’d reminded Dr. M. that I’d wanted Ignatius in a jar, and he had dryly responded, “It would have taken a bucket!”

At one point during the week when Dr. M. had seemed a little discouraged about the tenaculum incident, it occurred to me that I hadn’t told him how I felt. So I did — even only few days later, even with gas pain and incision soreness, I could tell that my lower back tiredness, ache, and pain were 1,000 percent better and that the surgery had made a huge difference. He quite brightened and said, “That’s good!” Even experienced surgeons need reassurance. It is true, however — I wasn’t buttering anyone’s bread. The disgusting hard spot underneath my navel is gone, my uterus is no longer the size of an eighteen-week pregnancy, I don’t feel bulky and bloated, I don’t have a constant urge to urinate, and wonderfully, my back and legs feel normal without the pressure of the fibroid against my spine and nerves. In return, my already grotesque appendectomy scar is even more distorted, my activities are a little restricted for a longer period than planned, and I’ll probably feel the pull of scar tissue for a longer time, as I did after the appendectomy. The pain, fever, and tedium were worth the long-term results. At my age, I don’t think it’s likely I’ll grow another Ignatius.

Of course, the truly terrifying parts are yet to come — the bills.

Related posts:

The plot to murder Ignatius, part one — June 14, 2008

The plot to murder Ignatius, part two — June 15, 2008

Ignatius, the friendless fibroid — July 26, 2008

18 August 2008: The day of reckoning for Ignatius — August 26, 2008

Snuffed but not forgotten: Ignatius, the large, dead fibroid — April 29, 2009

Where’s Ignatius? (or, find the fibroid) — June 16, 2009

Ignatius the tenacious — June 21, 2009