We have bees at work! at work.

Coexisting with bees in cities is easy and natural. After all, honey bees are just one of a number of pollinators like butterflies, bumble bees, and wild bees with whom we already share our urban spaces.

I have passed by and seen but not seen this sign thousands of times from the bus. Finally I noticed the exchange telephone number: FA4-4200.

All this time I never noticed the florist is gone, which is obvious. They moved in 2001.

Florist shop replanted

Art Miller’s Florist Shop, 1551 E. Hyde Park Blvd., a 50-year-plus tradition in Hyde Park, is budding all over with both new owners and a new location.

Don Eskra and Linda Wiening, who bought Miller’s last year, have swapped the shop’s beleagured location beneath the overpass on Hyde Park Boulevard for 1521 East 55th Street, a move that was not without its trials.

“Our phones were all messed up for about a week, and people thought that Art Miller’s had gone out of business,” Wiening said.

Eskra had previouslv owned a group of flower shops in Bridgeport that he sold for Art Miller’s.

Hyde Park Herald, June 13, 2001

7/20/2023 update: Someone in the Hyde Park group posted “Chicago Telephone Exchange Names.” FA was Fairfax.

After months of abnormally dry to severe drought conditions, Chicago had a near record “rainfall event” the weekend of July 1–2, especially on Sunday.

To me, it seemed like a normal rain, but I don’t have a personal basement to worry about. I gave up any thought of outdoor activities and stuck to reading, TV, etc. I figured I’d be grateful if this rain, plus a few others that preceded it, would put a dent in the severe drought conditions.

As of July 11, Chicago was still abnormally dry, but look at the difference.

June 10, 2023:

Same area, July 9, 2023, a little less than a month later:

When I noticed the orange light on my weather radio flashing the evening of July 12, I was hoping for beach hazards or at worst a flash flood watch, but, no, it was a tornado watch. As the sky got darker, it flipped to the red light — tornado warning. Not long after that, the sirens started — an eerie sound in the eerie premature twilight.

Over the next hour or so I saw several reports of tornadoes, starting with Summit in the southwest suburbs. Then it seemed like they were everywhere — southwest, west, north.

The sky brightened for a moment, then darkened, then brightened again just as another brief deluge descended. I looked — yes, there was a rainbow (and a very faint second mirror image rainbow). It faded, then reappeared, or maybe it was a second one in a similar spot. The second, with a faint mirror image like the first, was the full arch, which I couldn’t capture from my window.

It faded as blue sky appeared to the east, then pink from the setting sun tinged the clouds that had piled up.

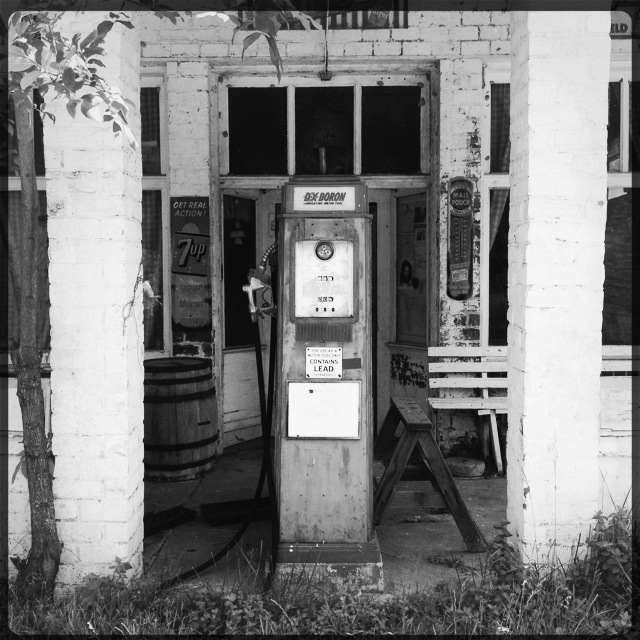

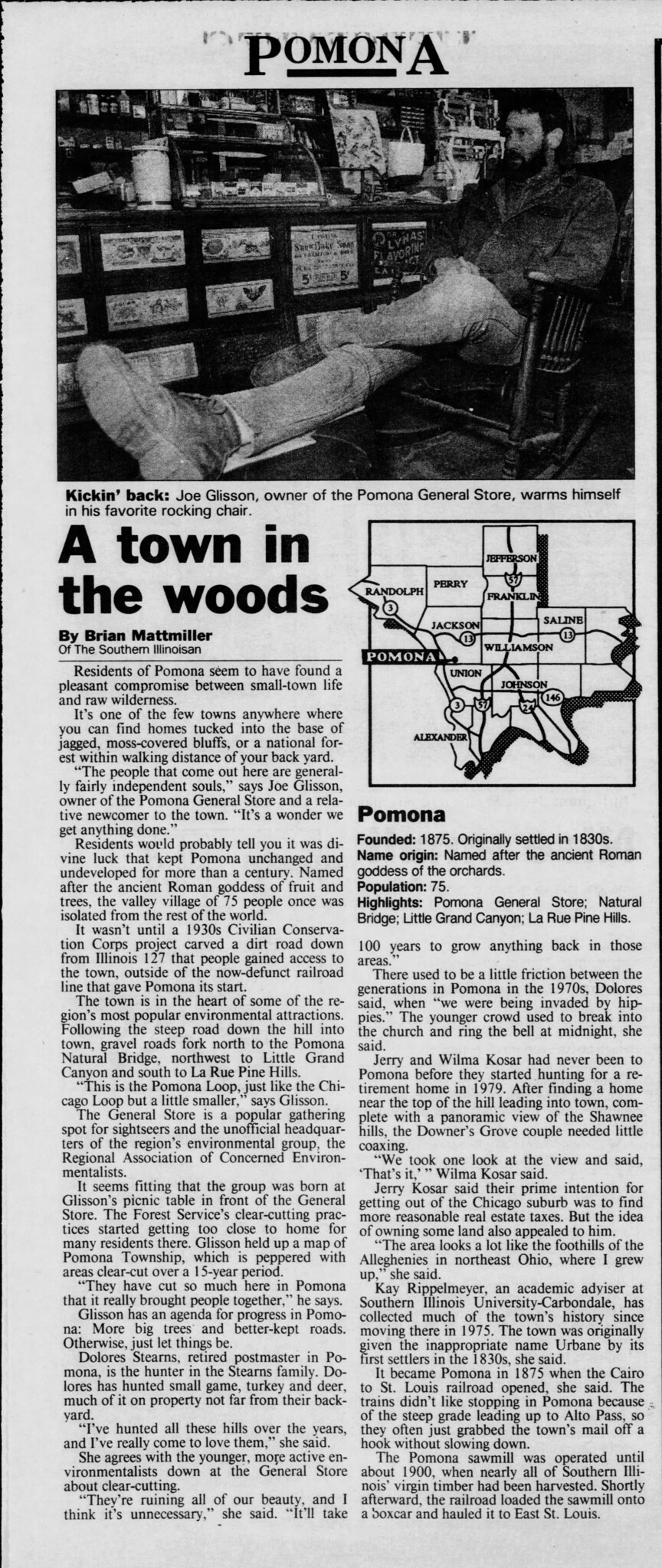

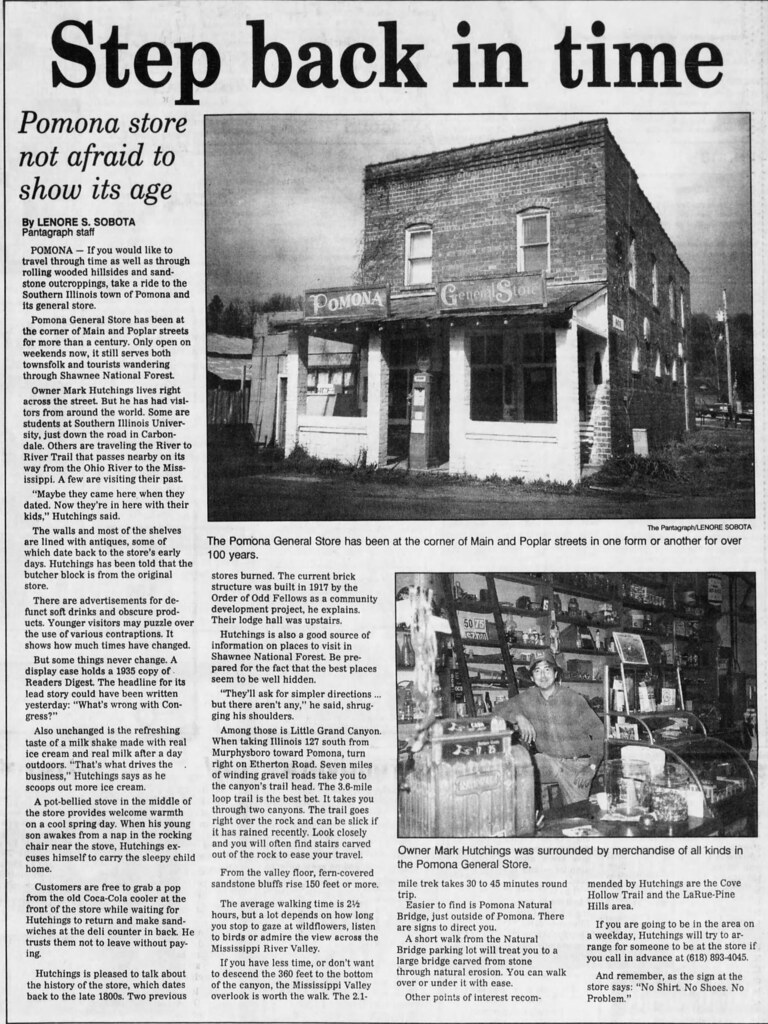

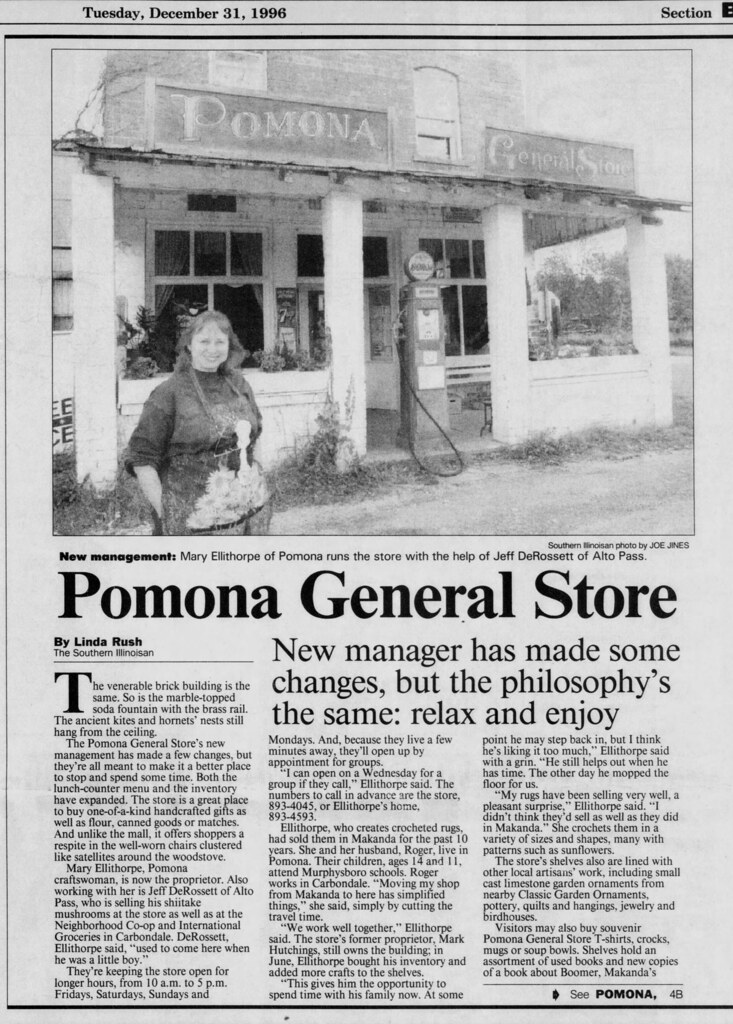

On a 2013 visit to Shawnee National Forest in southern Illinois, I came across this gem at a crossroads near the Pomona Natural Bridge. Finding the photos again, I was curious about what this building had been and when it closed for good.

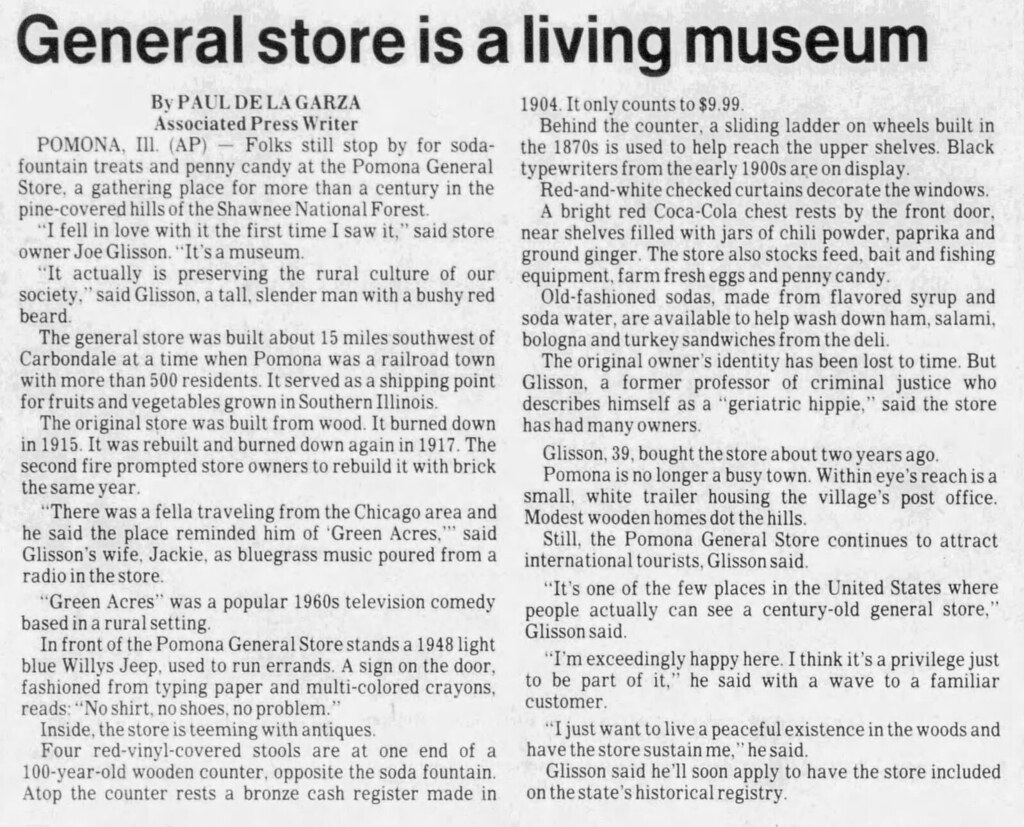

It’s the Pomona General Store, and even the New York Times published an article about it.

At an Illinois Country Store, Nostalgia Sells Best

July 15, 1987

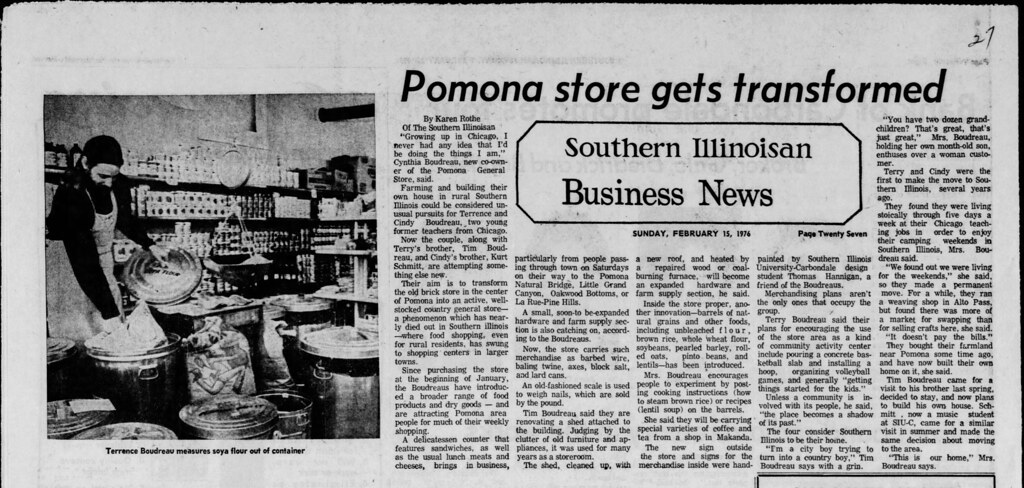

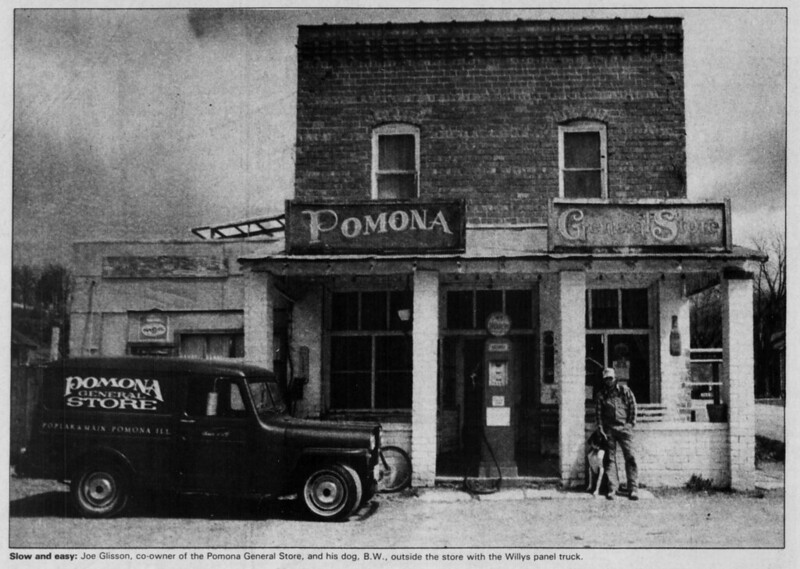

The store was built in 1876 when Pomona, about 15 miles southwest of Carbondale near the southern tip of Illinois, was a railroad town with more than 500 residents and a shipping point for produce.The original wooden store burned down in 1915. A rebuilt store burned in 1917, and a brick store was built the same year to replace it.

I dug around newspapers.com and found a little of the store’s most recent history starting with the 1970s, when media mentions picked up. Over the next couple of decades, the store changed hands a few times. It also attracted attention as a relic — an old-school general store in an era of big box stores. For years it seemed to be a center of Pomona community. Even after it closed, its location was used for community events like bake sales.

A few people have mentioned surprise the gas pump was in place (as of 2013) as they are “very collectible.” I found a photo from 2022 that shows the pump still there. Perhaps the Pomona community keeps a watchful eye on it.

The store must have closed between 2000 and 2002. Over the next decade or so, it deteriorated more than I would have expected. I’m reminded of what I saw of the TV series “Life After People,” which speculated how plants, wildlife, and other forces would eat away at the infrastructure and buildings humans have wrought after they were no longer maintained.

I imagine someday in Pomona the ivy will finally take over the store, and time will erase the memories.

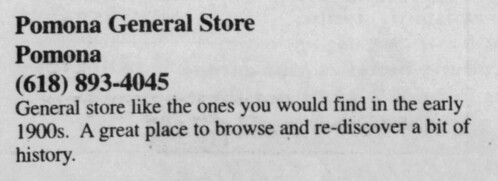

On August 12, 2021, the United States Postal Service issued “Backyard Games,” sure to appeal to the nostalgic baby boomer like me.

Per USPS:

The stamp pane features eight unique designs illustrating eight backyard games:

- badminton

- bocce

- cornhole

- croquet

- flying disc

- horseshoes

- tetherball

- variation on pick-up baseball

Each design emphasizes the movement of the game pieces, giving a dynamic quality to the artwork, with a simplified style that evokes the nostalgic feeling of playing backyard games as a child.

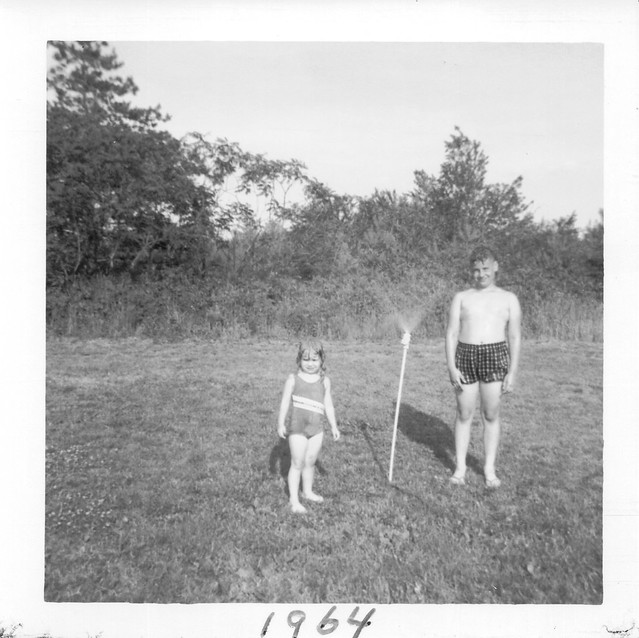

Later my brother scanned some old slides, likely taken when he was home from the Army. They included photos of two of my aunts and me playing Pop-A-Lot, a backyard game from Tupperware I’d half forgotten.

Our trailer was at the end of a row, with a field beyond. My dad and the trailer park owner had an understanding. We could use the field next to the trailer rent free if we were willing to mow and maintain it. Our yard on the other side was small and shrank more when my dad planted a shed in the middle of it, so this was a great perk.

The field offered us two to three times the space, up to the point it turned into an uneven, weedy, wet depression. My dad had borrowed a glider, which he put on that side of the trailer along with a table and umbrella. (Later he moved them behind the shed for shade. Your choices were roast in the sun all afternoon on one side, or get eaten alive in the evening shade by mosquitoes on the other.)

Dad put up a trellis or two for morning glories and, later, a wild rose he dug out of the wet depression. He got enormous tires to use as raised flowerbeds. He planted a rectangular garden with flowers like zinnias and vegetables like bell peppers, anchored by Virgil’s Arbor Day ash tree at the southwest corner.

A light pole next to the trailer sported a board with horseshoes tacked to it. I have no idea where they came from. We may have used them once or twice. I loved the idea of having horseshoes, once associated with luck, and wondered if ours had been worn by a horse.

Of course we tossed a flying disc around (maybe a Frisbee). We played badminton; I remember I hit the birdie too hard like it was a tennis ball. Virgil and his friends played a few games of pick-up baseball and even flag football. They were surprised that I could sometimes hit the ball almost as far as the woods. Not bad for a girl eight years younger than her brother and his friends. The trailer park also had a basketball hoop stuck to a light pole in the field. The last time the basket went missing it wasn’t replaced. By then, most of the people who would have used it were gone.

The backyard games we played that aren’t on the list: Jarts and Pop-A-Lot.

The last (and possibly first) time we broke out Jarts, my brother (if I recall correctly) speared the top of his friend’s foot. It was quite gory.

Pop-A-Lot’s packaging said:

Could “safe” has been in response to Jarts, which were as unsafe as anything could get?

I recall it was fun. It looks like my dad’s sisters liked it too (as long as it didn’t muss their hairdos).

Although it wasn’t a game, the other backyard activity we indulged in involved water. For a while I had a wading pool — two, actually, one boat shaped and the next round. I outgrew both quickly. We also had a sprinkler attachment for the hose that spun around — it was great fun. The only reason I can think of for not using it more was not wanting to waste too much water.

Sadly, by the time I was old enough to play some of these games, my brother had left for the Army, and his friends had dispersed to begin their own futures. The demographic of the trailer park changed, too, with the families moving out and retirees trying to stretch their pensions moving in.

The Forest Preserve District of Will County’s “Winter Wonderland” at Messenger Woods reminded me of Pop-A-Lot and backyard games, even if they weren’t all “real” games. I could see myself working to consistently get a plushie snowman’s head into a basket on my head. After all, it’s fun, safe, and develops coordination.

One of my favorite stays may have been the shortest. It wasn’t a choice, but came about serendipitously.

The drive from Superior, Wisconsin (Amnicon State Park), to Kabetogama, Minnesota, started late, after the summer sunset. J and I spent eternity passing through what, at night, looked like sparsely populated areas. It was a relief (literally) to find a roadside bar. When we arrived at the planned destination, it was probably after 1 a.m. — late enough to find the windows dark, the door locked, and the phone unanswered. It turns out family-run lodges aren’t like a Hilton or Marriott, with 24-hour desk attendants. Oops.

I was too tired to sit up or think, but I didn’t fancy trying to sleep in a car not designed for camping. Somehow I came up with the thought of calling around, which was not easy to do because cell coverage was weak and intermittent. It was difficult both to find places through Yelp! or websites, then to make phone calls. I can’t remember now, but I think i made some calls that went unanswered before I got to Arrowhead Lodge (still in the “A” section). A tired-sounding woman answered.

I quickly explained the situation and probably warned her the call might drop. She said she had space for us — hallelujah! When I said we’d be right over (before she changed her mind), she answered, “No hurry. I have to get dressed.” Yikes.

Arrowhead Lodge is 2.5 miles, or 7 minutes, from Sandy Point Lodge via dark rural roads. I didn’t know if I could stay awake that long. We made it after 2 a.m.

I stayed in a no-frills room with several beds to choose from, a fan, and maybe a radio — my memory is dim. The floor had a shared bathroom, in which several people (maybe even over time) had left assorted toiletries. I didn’t mind — all part of the adventure and shared outdoor experience. I didn’t see anyone, though, and several of the rooms were empty (open doors).

In the morning (a mere few hours later), we ate a great breakfast (al fresco, I think). Our perch overlooked Lake Kabetogama, which I’ve since learned is “Kab” to the locals, plus a flock of white pelicans. If we hadn’t been due to join a Kettle Falls cruise, I could have stayed there the rest of the day, but we left reluctantly. At the cruise departure point, J. realized his camera bag was missing. We raced back to Arrowhead to find our host keeping an eye on it while it took up a barstool. With our wee hours arrival and forgetfulness, she must have thought we were quite the characters.

Sadly, I took only a few poor photos at Arrowhead Lodge.

Later the owners, including the poor soul I’d woken up, sold the resort. The new owners have restored Arrowhead. which had deteriorated over the decades since its 1931 opening in the extremes of Minnesota’s climate. The first part of the video below shows the restoration effort and is well worth a look.